Funny how words change their meaning over time. Back in the 1300s “silly” started out meaning “blessed” and “pious”. Over time its meaning morphed to “innocent” to “harmless” to “pitiable” to “weak” to “foolish”. Quite a step down from “blessed”.

Makes me think of the word “sustainability.” It went from meaning “the quality of being sustainable at a certain rate or level” to “the property of being environmentally sustainable.” Now admittedly environmentalists will recite the “three legs of the stool” and say that, whatever you do, it has to be sustainable environmentally, socially, and economically. But nobody really means that. Not really. The economic part of sustainability is just lip service. The environment trumps.

Think about all of the third-party groups out there that have set up criteria for sustainability performance in different industries. You will be hard pressed to find one that includes EBITA or PROFIT along with emissions and carbon neutrality as measures of sustainability. Take the “circular economy” mantra as an example. Having a business model that reuses everything, generates no waste, and is environmentally neutral, and socially beneficial is a wonderful idea. If you are starting with a blank sheet of paper. But virtually all businesses are based on a XXth century business model that does not measure—let alone value—those outcomes. And virtually all businesses don’t have the luxury of foregoing revenue—let alone profit—while they reinvent themselves. As a result, the expectation being placed on business leaders is akin to being asked to redesign a car. While you are driving it. At ninety miles an hour. At night. On a dirt road winding along a cliff. Narrow road. Very narrow. In a snowstorm. Economically sustainable—don’t be silly.

Having said all that, becoming environmentally sustainable is a bona fide objective. Certainly no one can disagree with it. So how can business leaders tackle it, while staying economically sustainable? I’m going to propose two broad themes that are going to define sustainability success in the XXIst century. And there’s good news bad news, depending upon what kind of leader you are.

Life Cycle

“Sustainability” is in the eye of the beholder and there are a lot of beholders out there eyeing your business. At its broadest, it holds you accountable for the environmental and societal repercussions of your business. But the devil is in the detail.

Environmental performance is not a single metric but rather a basket of individually complex, interdependent variables: climate change, acidification, eutrophication, photochemical smog formation, human, marine and aquatic toxicity, to name just a few. Improving one often exacerbates one or more of the others.

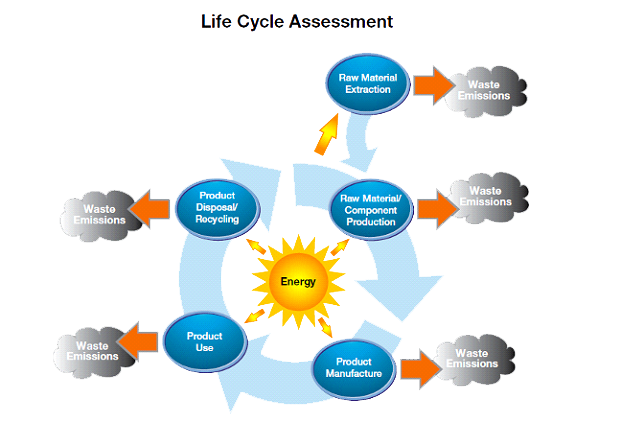

Societal performance has been interpreted to cover everything from child labor to human health threats. And you are held accountable for all of these impacts regardless of where they arise in your value chain — from raw material extraction to manufacture to use to end-of-life of your products.

How to even begin?

At the risk of sounding trite, you can’t measure where you are going until you know whence you came. You need a baseline. What does that entail? Everything. I mean EVERYTHING. From the raw materials you purchase through the manufacturing of your products through their useful life and their end-of-life fates. All inputs and outputs. Energy, materials and water in, waste and emissions out. Transportation as well. Everything. For every facility. You need data if you are going to measure change. This isn’t just writing a check. This is ongoing headcount and measurement systems, standardized across all of your facilities. Sustainability costs.

Why can’t we just focus on climate change and call it a day? Isn’t that the most critical issue? Ok, let’s look at climate change. Without throwing several pages of citations at you, many very credible environmental thinkers argue that the only way we are going to avoid climate change catastrophe is through the adoption of (wait for it) nuclear energy. So why don’t we? Well, there’s Three-Mile Island, Chernobyl, and Fukushima to start. And what are they about? Human, marine and aquatic toxicity. Tell me, how much climate change is worth how much toxicity? And there’s the rub. Sustainability isn’t just a single thing. It is a basket of different environmental impacts: climate change, eutrophication, photochemical smog formation, human-marine-aquatic toxicity, to name a few. And each of these impacts is defined by three axes: duration (seconds or centuries), severity (sniffles or death), coverage (your living room or the entire planet). And they are all interrelated, witness nuclear energy. You decrease one but, in doing so, you inadvertently increase another. Whack-a-mole.

The same challenge presents itself across your lifecycle. In more than one case, I have seen an increase in environmental impacts during manufacturing that has produced a product with dramatically reduced environmental impacts during its useful life. The net effect is a reduction of environmental impacts. But if you are only looking at smokestacks and drainpipes, you won’t see it. And many environmental groups look only at these, or only at climate change. So you don’t see the whole picture until you do a lifecycle analysis of your business. Sustainability costs.

Ok, so you’ve got a lifecycle analysis. But, as we’ve shown, the impacts are interrelated as are the phases of the lifecycle. So, what’s the right thing to do? Every good decision has a bad consequence, or so it seems. Welcome to adulting. I don’t remember saying that this was easy. But making hard decisions based on sound data is always better for the environment as well as your business than the alternative.

Schöpferische Zerstörung

What the heck is that? This is Joseph Schumpeter’s theory of creative destruction. Basically, for anything new and novel to emerge, it has to destroy whatever it is replacing. Nothing new, really.

Except that… things are changing.

Think about how business planning currently works (or doesn’t).

In theory…

A good business strategy provides a future plan of action to generate profit extending beyond the life cycle of a product or service. It is based upon insights born of an ongoing, thoughtful study of the:

- Strategic Landscape: critical uncertainties that will change the future business environment in which the industry operates, such as disruptive technologies, societal shifts, demographic changes, economics, etc.

- Market Landscape: critical uncertainties that in the future will impact and modify the industry in which the business currently competes.

- Competitive Landscape: critical uncertainties about the future behavior of individual industry players.

Using geopolitical terms, a more accurate way to describe these three categories are as forms of “intelligence,” since intelligence is the acquisition and application of knowledge.

How far into the future a strategy looks depends upon the length of the product or service life cycle. For software, it may be as little as two years. For toothpaste, it may be five years. For oil, it may be 50.

Strategy isn’t a static event, but rather a continuously evolving process altered as new intelligence emerges that impacts the insights upon which the strategy is based.

In practice…

Too many business strategies suffer from one—if not all—of the following flaws.

- Shortsighted Intelligence: Too many strategies fixate on the immediate competitive landscape, concern themselves too late with the mid-term market trends and completely ignore the larger long-term business environment change. Remember Kodak?

- Misdirected Metrics: Given bad intelligence, too many strategies set performance objectives based upon internal performance without regard for how the market pie is growing, shrinking or shifting. From this comes the ubiquitous hockey stick strategy. Since internal performance objectives are unrelated to external market behavior, they are rarely met. This breeds cynicism which, in turn, undercuts employee commitment to meet next year’s hockey stick.

- Forced Process: Too many strategies result from a “hot house” process: an intense annual session in a hotel or corporate conference room where everyone involved loses the will to live before the cake is finally baked. And after it is baked, it goes on the shelf and no one bothers to eat a slice until the next year’s bakeoff. No time is afforded for teasing insight out of the intelligence and there is certainly no expectation that reflecting upon that intelligence is an ongoing, every-day part of a manager’s position description.

- Top-Down Culture: Too many strategies are imposed from the top down rather than constructed from the bottom up. They are based largely upon what the CEO or the VP feels is going to happen and are unencumbered by solid intelligence analysis. Invariably, the false assumption is made that the underlying business model is durable which, in turn, leads to misdirected metrics. The sad irony is that the more successful a business has been in the past, the harder it is for leadership to see that the business model may fail in the future. This is partly due to arrogance, but it is also due to laziness. Good planning is hard brainwork, and it is far easier to mindlessly continue doing what has always been done. “Managers do things right. Leaders do the right things….”⦁ [1]

“Houston, we have a problem…”

All of this would be bad enough if nothing else was happening. But something else IS happening.

Up until recent years, business environment and industry change—with a few exceptions—was evolutionary. This gave businesses the luxury of time to react and course correct before it was too late.

That is no longer the case. The rate of change has accelerated in virtually every industry, fueled by a perfect storm of societal forces and disruptive technologies. The data already shows the consequences of this acceleration. In 1935, the average lifespan of a Fortune 500 company was 90 years. In 2016, it was just 18[2]. Between 1970 and 2015, the average lifespan of all publicly traded companies nearly halved[3]. Unlike the Fortune 500, midmarket companies have never had the luxury of a deep planning bench. The accelerating decline in longevity makes strategic planning more important today than ever before. Companies no longer have the luxury of time to react; increasingly they must anticipate if they are to survive, let alone prosper. We are approaching a maelstrom of Schöpferische Zerstörung.

So, how does a business cope with this whirlwind of change? On the societal side, how do you digest and prepare for deflation, urbanization, and deglobalization, as well as changing consumer and employee behavior? On the technological side how do you cope with 3D printing, nanotechnology, automation, new materials, the Internet of Things, big data, artificial intelligence, blockchain, synthetic biology, and digital manufacturing?

Consider the business environment and market ramifications of a declining population as an example. A growing body of demographic experts now believe that global population will peak in our lifetimes—and then decline[4]. What happens to your business—to your industry—when there are fewer young workers with different career aspirations, markets are shrinking and the majority of consumers are over the age of 50?

Digesting strategic, market, and competitive intelligence to forecast this future is hard. More adulting required.

A Perfect Storm… Societal Change

- Health & Wealth—increasing wealth and greater longevity

- Urbanization—dramatic urban population growth in the developing world

- Deflation—shrinking, ageing populations

- Deglobalization—increasing political unrest within developed world working classes

- Consumer Behavior—shifting developed world consumer patterns

- Employee Behavior—shifting millennial employee expectations

Technological Disruption

- Energy—growing cheap ubiquitous off-grid energy

- Automation—changing the role of labor

- 3D printing—changing how things are designed and where they are made

- Nanotechnology—changing the scale at which things are made

- New Materials — expanding material performance attributes

- IoT+BigData+Analytics+AI — increasing insights to be gained from data

- Digital Factory — redefining how manufacturing is done

- Blockchain — redefining how transactions are done

- Synthetic Biology — redefining how things are designed

Takeaway

So what do these two cosmic themes mean for your business? Well, here’s the good news bad news. We talked about the near impossibility of retooling an old XXth century business model to accommodate the expectations of sustainability. The good news bad news is that your old XXth century business model is on its way to being destroyed by XXIst century disruptive forces. If you don’t reinvent yourself, your competition will do it for you. Soon. And, in reinventing yourself, you have the opportunity to factor in sustainability as part of your core business design which includes profit.

I don’t remember saying that this would be easy.